It’s Time to Make the News

I

A few weeks ago I wrote a few paragraphs questioning the legitimacy of traditional media outlets (e.g., television news, print newspapers, print news magazines, etc.) when compared to newer outlets (e.g., blogs, Internet-only news outlets, etc.). The argument has been that the bigger outlets are “professional” when compared to amateurs with blogs and have more access to getting to the bottom of a story.

...Today during lunch I was discussing the state of television news with my friend ***** (I’m protecting his identity because I don’t want his reputation to be sullied if it should become known that he associates with me) and, given that his line of work is behind-the-scenes stuff for television production (i.e., video, sound, production assistant work, etc.) we found ourselves discussing the current state of television news: Is it information or infomercial? I made the argument that while the best description would be “infomercial,” we have to place the blame for it being this way on the consumers. After all, if more people were demanding informative, in-depth investigations on major stories, the networks would adjust their presentations to reflect this.

...Instead, the majority of television news viewers are tuning in to be entertained. They’re more interested in Paris Hilton’s jail sentence than the estimated 300,000 barrels per day that have disappeared over the last four years in Iraq.

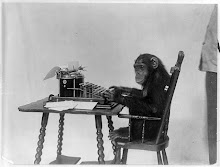

...This isn’t anything new, though. As far back as the late-1800s the country had to deal with yellow journalism, in which the news was essentially invented. From journalists like Joseph Pulitzer to newspaper owners like William Randolph Hearst, we saw fiction pushed as fact in an effort to sell a few more papers.

II

I hadn’t planned on defending conservative radio blowhard Rush Limbaugh, considering that when I was posting on my old blog I lambasted him for railing against drug users while he himself was addicted to prescription pharmaceuticals, but I’m quite concerned when “professional” news services prove to be more amateurish than true amateurs.

...A few weeks ago, in what was either a sign of incompetence or intentional deceit, neither of which can be defended if one is passing oneself off as being “professional,” a television news station in California arrived late to the party and ran a story about a parody song entitled “Barack the Magic Negro” which was sung to the tune of Peter, Paul, and Mary’s “Puff the Magic Dragon” and was aired on Rush Limbaugh’s radio show. A news story on CBS 13 about the song was chock full of errors, including failure to explain the origins of the tune (which were comments made by Al Sharpton, Senator Joe Biden, and an L.A. Times column from David Ehrenstein using the term “Magic Negro”) and the use of a homemade video for the song found on YouTube that was presented as an officially-made video (in reality no officially-made video for the parody exists).

...Fast-forward to yesterday: The Houston Chronicle ran a piece from Andrew Guy, Jr. entitled “Is Limbaugh Above the Law?” in which he questions why Don Imus and other disc jockeys have been fired for racist remarks, but Limbaugh hasn’t for the “Barack the Magic Negro” parody. In the column, Guy ponders why there are no protests, prepared statements, press conferences, apologies, or even outrage from the public. He also perpetuates the CBS 13 error by referring to the homemade YouTube video as “Shanklin’s video” (Shanklin being Paul Shanklin, who wrote the lyrics to the parody).

...More humorous in the piece is Guy’s interview with Ehrenstein, whose column helped to inspire the parody in the first place. Ehrenstein says that he’s “not sure why no one else has really talked about it.” Perhaps it’s because the song was inspired by actual remarks by Ehrenstein?

III

As I had mentioned earlier, I don’t consider myself a follower or an apologist for Rush Limbaugh. I do, however, question why and how stories that could be easily investigated by major news outlets are falling prey to slipshod reporting and armchair journalism (i.e., if one outlet reports something—erroneous or otherwise—another outlet simply picks up the story and runs with it; if it’s sensational, it must be good).

...Moreover, keeping with the notion of ideology, I find myself wondering if ideology has become a determining factor in reporting, similar to the yellow journalism of the 1890s. While I don’t buy into the idea that there exists some kind of giant “liberal media” or “conservative media” conspiracy (I’m of the belief that people will find an enemy whenever they hear something that they don’t like—no matter if there is factual basis to the story or not), I do think that the possibility exists that some people are willing to misrepresent facts in an effort to promote their own beliefs. Several years ago author Michael Bellesiles showed us that you can actually garner support for fraud so long as your supporters believe that your overall message is a just one.

IV

In the end, it’s my firm belief that Limbaugh isn’t getting a free pass on this issue in the way that Guy suggests in his column, simply because a parody based upon actual remarks from politicians, so-called civil rights leaders, and newspaper columnists is vastly different than a stereotyped comment about looks à la Don Imus or a stereotyped prank phone call to a Chinese restaurant à la Jeff Vandergrift and Dan Lay.

...Had Al Sharpton never questioned Barack Obama’s blackness, the parody might be a true controversy. Had Joe Biden never called Obama “the first mainstream African-American who is articulate and bright and clean,” the parody might be a true controversy. Had David Ehrenstein never written that “it’s clear that Obama also is running for an equally important unelected office, in the province of the popular imagination—the ‘Magic Negro,’” the parody might be a true controversy. Unfortunately for Guy, those things actually occurred.

...I’d sooner argue that the biggest controversy of this story is the willingness of a professional news outlet to hype a story and include inaccuracies in an effort to sensationalize something that wouldn’t otherwise be as sensational.

...Then again, as William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer showed us, sometimes you have to lie a little to sell a few more papers.

References

• Houston Chronicle (screenshot 1; screenshot 2)

• International Herald Tribune

• PBS